Category: Wellness

Calling all 12-18 year olds! Book an appointment and let’s check-in and chat about your physical and mental health including stressors and goals. Winterberry is a safe and supportive space, let’s get you ready for back to school together.

Booking is easy, just click here to visit our online appointment page.

Photo by Parker Gibbons on Unsplash

At Winterberry we encourage you to protect yourself from COVID-19 if you are in a high risk category. We are opening up evening vaccination appointments to make getting your shot easy and quick.

You are at high risk if you are any of the following:

• Adults 65 years of age and older.

• Adult residents of long-term care homes and other congregate living settings

for seniors.

• Individuals 6 months of age and older who are moderately to severely

immunocompromised (due to an underlying condition or treatment).

• Individuals 55 years and older who identify as First Nations, Inuit, or Metis

and their non-Indigenous household members who are 55 years and older.

As part of our ongoing commitment to help our patients live their best life we are sharing the full USA Today series on “Rethinking Obesity”. The following is #5 in the series.

ILLUSTRATION BY TRACIE KEETON/USA TODAY; AND GETTY IMAGES

Karen Weintraub USA TODAY

Published 5:01 AM EDT Jul. 26, 2022 Updated

Editor’s note: Part 5 of a six-part USA TODAY series examining America’s obesity epidemic.

For two decades, Charleah Torres-Vega, 43, refused to donate her favorite dress – a blue strapless number – hoping it would someday fit again.

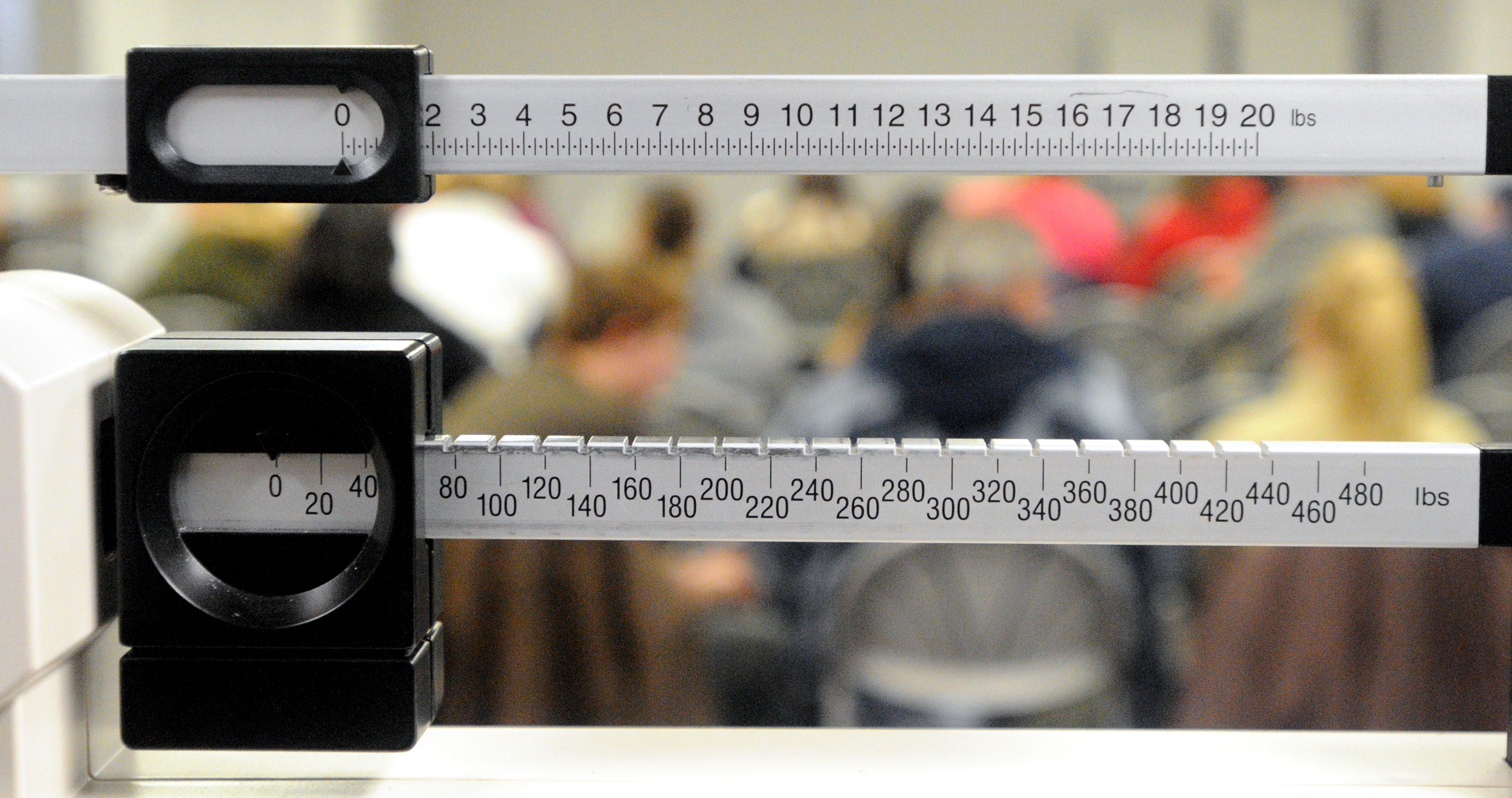

After giving birth to her fourth child, the 5-foot-4 Boston resident weighed 236 pounds, or 62 pounds above the cutoff for clinical obesity.

“It was a shocking number and also very frustrating,” she said.

For decades, medicine has had little to offer people such as Torres-Vega, even as the majority of Americans added extra pounds.

There’s no other common disease for which only 3% to 4% of patients can get evidence-based treatments that are actually helpful, said Torres-Vega’s doctor, Fatima Cody Stanford, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

“It’s hurtful to me to see that this is how we treat patients with obesity,” she said.

Finally, that’s starting to change.

Rethinking Obesity

Despite decades fighting America’s obesity epidemic, it’s only gotten worse. To try to understand why, USA TODAY spoke with more than 50 experts for this six-part series, which explores emerging science and evolving attitudes toward excess weight.

As the scientific understanding of weight loss deepens, the tools for addressing it are improving.

A year ago, an injectable diabetes drug called semaglutide, from Novo Nordisk, won approval from the Food and Drug Administration. It offered three times the weight loss potential of existing drugs: 15% of a person’s body weight.

Another drug, tirzepatide, was approved in mid-May for the treatment of diabetes. A study released in June showed it’s also effective at helping people lose weight. Virtually all 2,500 trial participants lost at least 5% of their body weight over a year and a half. More than half lost 20%.

With mostly manageable side effects, these medications and more in the pipeline have the potential to transform the nation’s obesity epidemic, said Dr. Katherine Saunders, a weight loss specialist at the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

Dr. Katherine Saunders, a weight loss specialist at the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine

It does feel like we’re at an incredibly exciting time where the medications we have available are helping so many people to lose very clinically significant weight.

“It does feel like we’re at an incredibly exciting time where the medications we have available are helping so many people to lose very clinically significant weight,” Saunders said.

The big question is whether people will be able to access them – or want to. The new medications are expensive and often not covered by insurance. Staying healthy also requires regular exercise and maintaining a balanced diet, Stanford and others said, so the shots aren’t a simple solution.

As with drugs to treat other chronic illnesses, anti-obesity medications are intended to be taken for a lifetime. Stop taking the weekly injections, doctors say, and biology will ensure the pounds return.

As a medical student, Stanford was taught all about rare diseases she has never seen in decades of practice. But her professors spent almost no time talking about a condition that now affects at least 40% of Americans.

She was drawn to the medical treatment of obesity in part because she can make a profound difference in her patients’ lives and in part because she’s Black.

“I could see the disproportionate impact,” Stanford said. Black women have the highest rates of excess weight in the United States: More than half are considered to have obesity, and 30% more meet the definition of overweight.

“I felt like I needed to be at the front lines of being able to address this,” she said.

Taking on the challenge

Torres-Vega is a rare exception. She was able to lose weight through force of will.

In 2019, her primary care doctor said her blood pressure was on the rise, so she went back on the Beachbody diet and exercise plan. She committed to make more time for herself and stay disciplined.

She fed her family chickpea protein pasta and cauliflower rice and switched to 99% fat-free ground turkey instead of ground beef for her spaghetti sauce.

“I still eat everything I love,” she said, even if it’s in a slightly different form. “I don’t believe in deprivation.”

She ate more fresh, organic vegetables and fruit, made sure she had lean protein, controlled her portions and started accounting for the bites she took as she cooked nightly meals for her family.

Her husband also has lost weight, and she’s teaching her children good food habits.

“Improving our healthy relationship with food has been a journey,” she said.

By late last year, the paralegal and Beachbody coach managed to reach her longtime goal of 160 pounds, her high school weight. The skinny jeans she had bought for her 30th birthday were so baggy she could fit her whole body in one leg.

But she was terrified it would all come back. Again.

Rebound is a concern after all forms of weight loss. Sometimes people bounce back and end up even heavier than when they started, said Dr. William Dietz, director of the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness at The George Washington University.

Someday, researchers may find a “switch” in the brain or the gut that can be reset so formerly heavy people won’t have to keep fighting those extra pounds forever. Until then, Dietz said, medications are probably a lifetime commitment.

The price of significant weight loss

The full anti-obesity dose of semaglutide, sold under the brand name Wegovy, lists for $1,350 to $1,700 a month, typically costs $1,600 to $1,700 a month, though some stores charge as much as $6,000.

Even at that price, Novo Nordisk hasn’t been able to keep up with demand.

The company put advertising and new prescriptions for weight loss on hold late last year. In a memo posted to its website, Novo Nordisk said it can supply maintenance doses for those already on the drug but has stopped providing low-dose ramp-up prescriptions. Shortages, it said, will “continue into the second half of 2022 when we expect to stabilize supply.”

Eli Lilly, which makes tirzepatide, hasn’t yet set a price for weight loss, though it costs about $1,000 a month for the same dose that treats diabetes. The company has pledged to make it accessible to treat obesity.

At the moment, most insurance companies and Medicare don’t offer coverage for obesity other than some nutritional counseling.

Stanford said she is battle-hardened after years of fighting insurance companies. Massachusetts now has some of the best weight loss coverage in the country, she said.

Thanks in part to her efforts, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts offers visits with staff nutritionists for obesity without the need for prior authorization. Many of its plans provide reimbursement up to an annual cap for weight loss programs, according to spokesperson Amy McHugh.

But still, many Americans can’t get routine coverage even to see a nutritionist unless they’ve been diagnosed with diabetes or another serious weight-related problem.

New medications are changing the struggle to lose weight. Share this story.Share on Facebook

Medications are covered only for people with high BMIs or related health problems “consistent with evidence-based best practices,” said David Allen, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry group. “In some cases, plans may require individuals to partake in a period of behavioral modifications, increased physical activity and dietary changes.”

Obesity costs the U.S. medical system about $173 billion a year, roughly four times the amount spent annually to fund the National Institutes of Health. Medical bills for someone with obesity run $1,861 more than for a person weighing in the “normal” range.

Fundamentally, there’s not much incentive for insurers to cover weight loss treatments, said Dr. David Rind, chief medical officer for the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a Boston-based nonprofit that evaluates medical procedures.

Most treatments for diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol are inexpensive generics, so insurance companies would end up paying more if they replaced these with a costly weight loss drug, Rind said. He noted insurers are supposed to cover treatments that improve health, and “weight loss treatments can result in important health gains.”

Coverage isn’t needed for people with just 10 pounds to lose, said Dr. Louis Aronne, an obesity medicine specialist at Weill Cornell Medical Center in Manhattan, who helped lead the tirzepatide trials. But in less than 10 years, a quarter of Americans are projected to have a BMI of 35, well above the benchmark for obesity, and related diabetes rates will continue to rise, he said.

Those people deserve to have their medication covered by insurance now rather than having to wait to get sick, he said.

Older, inexpensive anti-obesity medications still have a role to play, too, Saunders said.

They don’t trigger anywhere near the kind of weight loss as the newer generation of drugs. Most can help people lose about 5% of body weight. But they can be useful for modest weight loss and in combination, as part of a comprehensive treatment plan.

Saunders provides the kind of intensive, personalized counseling that most Americans can’t access, but her company, Intellihealth, has launched a digital program called Evolve and a telehealth practice called Flyte that she hopes will spread her approach.

In her own practice, she starts with each new patient taking a detailed history of their weight gain and barriers to weight loss. She also runs a panel of labs to identify contributors to weight gain and ensure their kidney and liver functions are OK. Then she gives them feedback on lifestyle approaches they can try.

If they’ve already tried them all, she said, “then I’ll say ‘OK, you’re a good candidate for anti-obesity medication.'”

Why weight loss matters

Modest weight loss of 5% can improve some health metrics, like blood pressure and markers of diabetes, research shows. But even that amount of weight loss is difficult for most people to achieve through diet and exercise.

And it doesn’t always help. Famously, a trial of more than 5,000 participants with diabetes and either obesity or overweight was stopped after nearly a decade when weight loss of more than 6% failed to improve heart health.

Generally, though, more weight loss has been shown to lead to more improvements.

In a study of people with a BMI of 40, a 13% median weight loss led to a 40% drop in Type 2 diabetes and sleep apnea and a roughly 20% decline in rates of hypertension, high cholesterol and asthma.

Healthy weight tips

• Know that it’s not your fault if you’re carrying extra weight. The way the human body evolved, combined with easily available and low-cost processed food make weight gain likely and weight loss challenging.

• Fitness matters more for health than a number on a scale. Find physical activities you enjoy and commit to move a total of least 30 minutes a day, five days a week.

• Make sure to average at least 7 hours of sleep a night. Disconnecting from electronics for 90 minutes before bedtime can help.

• If you’re concerned about weight, prioritize not gaining more and the quality of foods you eat.

• Chose whole foods, like fruits, vegetables, nuts, healthy oils, fermented dairy products and fatty fish, which have a healthier mix of nutrients and make you feel fuller.

Reducing cancer risk requires people with obesity to lose about 20% to 25% of their body weight, according to a study in June. Until now, that kind of weight loss has been achievable only through surgery, though the new medications might get some people there.

(Studies of tirzepatide haven’t yet confirmed that weight lost with the drug leads to substantial health benefits, though “all of the metabolic parameters measured were improved,” Aronne said. Some research has found health benefits with semaglutide. About 75% of weight lost with both medications comes from fat and 25% from muscle, he said.)

Dr. Ali Aminian, who led the recent cancer study, was surprised to see that so much weight loss was needed to improve cancer risk.

This means it’s increasingly important for people to have a way to dramatically reduce their weight, said Aminian, a surgeon who directs the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic. Until now, that has been possible only with surgery.

Just 1% to 2% of people who qualify for weight loss surgery actually go under the knife.

Surgery remains an option

“Why are we not using the thing that solves many of the disease processes that are affecting our country?” Stanford asked.

Some of that lack of use is because of fear. In the earliest days of bariatric surgery, death was a very real risk.

Though death remains a slim possibility, safety has improved substantially, Aminian said. Almost all surgeries are now done through “keyhole” openings rather than large incisions in the abdomen.

The lack of insurance coverage also keeps weight loss surgery from many who would benefit. It typically runs $15,000 to $20,000, Aminian said.

To qualify for coverage, someone must have a BMI over 40 or a BMI over 35 with a serious weight-related health problem, such as Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure or severe sleep apnea. Someone 5-foot-5 would have to weigh more than 240 pounds and someone 5-9 more than 270 to reach a BMI of 40.

Although new medications are getting close, no other weight loss approach has proved as effective as surgically shrinking someone’s stomach and rerouting the small intestine. With surgery, people can quickly lose dozens of pounds and 30% to 40% of body weight, Aminian said.

They may regain some of that lost weight in the years after surgery, but unlike with dieting, the rebound is rarely complete, and fewer than 5% of patients end up heavier five to 10 years after surgery, Aminian said.

For most people, surgery improves obesity-related conditions such as asthma, hypertension, fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, heart failure, polycystic ovary syndrome, menstrual dysfunction, excess hair, arthritis and sleep apnea, Aminian said. Often, these vanish within a few months.

Weight loss surgery improves quality of life, and the 10-year death rate after surgery drops by nearly 40%.

Aminian would like to see insurance cover surgery sooner, before patients reach extreme levels of obesity and suffer severe health problems. Just as it’s easier to treat cancer caught at an early stage, so the health consequences of obesity are more treatable or preventable if weight gain can be stopped.

“If a patient is 500 pounds, 600 pounds with all those complications, sometimes you feel like it’s already too late to intervene,” Aminian said.

How the drugs work

Once people gain weight, something changes about the way their body self-regulates that makes it nearly impossible to go back, Aronne said.

Consuming too many calories too quickly overloads the nerves in the brain that receive signals from hormones, he said.

“As you get more damage there, fewer hormonal signals are able to get through and tell your brain how much you’ve eaten and how much fat is stored,” Aronne said. “As a result, your body keeps expanding your fat mass.”

After decades of struggling to understand this process, researchers have finally figured out how to manipulate two of those naturally occurring hormones, called GLP-1 (short for glucagon-like peptide-1) and GIP (for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide).

GLP-1 is a fullness signal and GIP seems to amplify GLP-1’s effect, Aronne said.

Still, one medication alone is never going to be the solution to obesity, Saunders said.

Obesity is a complex problem with many factors contributing to weight gain and multiple barriers that prevent weight loss, she said. “It’s all about optimizing diet and physical activity, and then we need as big of an armamentarium of medications as we can get.”

As with any medication, they’re not for everyone. Some people suffer severe stomach problems, though doctors who use them routinely say they can help patients work through most of them.

Dr. Zhaoping Li, chief of the Division of Clinical Nutrition at the University of California, Los Angeles, said stomach discomfort is part of how the drugs work. “That’s how it makes you not want to eat,” she said.

Saunders said she had one patient who was vomiting every five hours after taking the drug. Clearly, it wasn’t a good fit.

But for most people, symptoms can be controlled by fine-tuning the dosage of the anti-obesity medication and adding or eating smaller meals. “Treatment needs to be personalized and complemented by close monitoring,” she said.

Looking forward

The coronavirus pandemic helped Torres-Vega lose weight. Instead of spending time commuting, she was able to work out at home early in the morning. She had more time to cook. And with that extra time and growing kids, she was finally able to prioritize her own needs.

“Being able to shut out most of the world,” she said, “helped me have much success.”

But she wanted something in addition to her new attitude to help her stay in control of her weight.

In January, under the direction of Stanford, Torres-Vega began taking semaglutide. She has been thrilled with the results. She no longer eats mindlessly and has been able to disconnect food from emotions such as happiness, sorrow and boredom.

Unlike many patients, Torres-Vega said she has no side effects from the medication. She doesn’t mind that she’ll probably have to take the medications forever to keep her weight where she wants it.

She just wishes she had learned sooner to think about obesity as a chronic disease to be managed rather than as a moral failing. “That would have helped me not be so hard on myself.”

Torres-Vega’s medication sits at the head of a long line of potential new approaches to weight loss.

“There are other advances to come that are going to continue to improve outcomes,” Aronne said.

Semaglutide acts on one biological pathway. Tirzepatide acts on two. The next-generation drug, now in animal studies, acts on three and could offer even more weight loss potential, he said.

Aronne said he went into weight loss research decades ago to address suffering. He didn’t think it would take this long to help people. But now that he has effective medications to offer, he finds it incredibly gratifying.

“It’s fantastic when you can help people who want to be helped,” he said.

As for Torres-Vega, the blue strapless is now a regular part of her wardrobe. “I’m having fun dressing the body I’ve always wanted and worked hard to achieve.”

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

As part of our ongoing commitment to help our patients live their best life we are sharing the full USA Today series on “Rethinking Obesity”. The following is #4 in the series.

ILLUSTRATION BY TRACIE KEETON/USA TODAY; AND GETTY IMAGES

Karen Weintraub USA TODAY

Published 5:02 AM EDT Jul. 26, 2022 Updated

Editor’s note: Part 4 of a six-part USA TODAY series examining America’s obesity epidemic.

Nathaniel Louis Brown always loved his food, especially spaghetti and potatoes. On a typical night, he would eat three dinner-plates full. On holidays, Brown, 64, served himself on a platter.

He knew he should cut back, but he didn’t have anyone who cared enough to tell him to eat less. Plus, food helped him curb life’s stresses and his constant worry.

Then came the heart attack.

Brown’s life is far from perfect, but he wasn’t ready for it to end.

“I want to try to live up to 100, 120. I know that ain’t going to happen, but that sounds good to me,” said Brown, a former long-haul truck driver, factory worker and prison guard now living in Indianapolis.

The social, racial and economic inequities that people like Brown face help explain why the nation’s obesity epidemic remains so challenging.

It’s nearly impossible to change a lifetime of eating and exercise habits and stick with them, studies show. Many people like Brown live in areas where it’s tough to access healthy foods or exercise safely and affordably. The economics of eating in America make high-calorie foods an easy go-to.

People with obesity “are victims of the system they don’t control,” said Daniel Clark, a medical sociologist at Indiana University and the Regenstrief Institute, a research organization in Indianapolis. Instead of blaming people for being overweight, “we should be shaming the system and the industry that has profited from all these added pounds and poor health.”

You have enormous forces in society that benefit from people being overweight. The diet industry benefits. The health care industry benefits. The drug industry benefits. The food industry benefits.

Nutrition researcher Marion Nestle likes to ask a simple question: Who would gain if people weighed less and ate more healthfully?

In the U.S., she can think of only a few. “You have enormous forces in society that benefit from people being overweight,” said Nestle, an emerita professor at New York University. “The diet industry benefits. The health care industry benefits. The drug industry benefits. The food industry benefits.”

The cost of food pushes people toward extra pounds, said Adam Drewnowski, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington.

Fresh strawberries, for instance, offer about 40 calories for $1, while Halloween candy provides about 2,000 calories for the same $1, he said.

“It’s not that people are making wrong choices about what to eat,” Drewnowski said. “They are not even choices.”

Poverty and pandemic

The poorest people aren’t the ones who struggle most with obesity, Drewnowski said. It’s those like Brown, who work their whole lives but still need the cheapest options.

“I call it a visible symptom of economic oppression,” he said.

Rethinking Obesity

Despite decades fighting America’s obesity epidemic, it’s only gotten worse. To try to understand why, USA TODAY spoke with more than 50 experts for this six-part series, which explores emerging science and evolving attitudes toward excess weight.

Obesity concentrates in neighborhoods that have few financial resources as well as limited social capital, he said. “The effect is to concentrate poor health in a given area.” Those same neighborhoods probably lack medical care resources, he said. “It’s a downward spiral.”

In King County, Washington, where he lives, Drewnowski said obesity can vary by 600% depending on a person’s address. “A mile or two down the road, things change,” he said. “It’s amazing.”

Race is sometimes connected to these social factors, but not always. A cohesive, largely Blackneighborhood might have the resources to demand safe streets, parks and grocery stores with healthy food.

Mexican American immigrants are healthier for the first decade or so after they arrive in the United States, regardless of their income, Drewnowski said. It’s only after their children persuade them to switch to an American diet that the pounds start to creep on and health problems accumulate, research has found.

The coronavirus pandemic and its financial consequences made the situation worse.

Food insecurity, which affects at least 10% of the population, appeared to increase over the last two years, said Dr. Wudeneh Mulugeta, an internal and preventive medicine specialist at Cambridge Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School. Demand at his Massachusetts organization’s food bank doubled or tripled at the start of the pandemic.

His research shows that people who were food-insecure and lived unhealthy lifestyles before the pandemic – maybe they smoked or their diets weren’t great – were also at higher risk for gaining more weight over the past two years than their neighbors.

“Not everyone gained weight,” he said. But those who did were the most vulnerable to begin with.

Working for health

After the heart attack and two stent placements, it took Brown a few months to muster the energy and motivation to get out of bed.

Eventually he joined Healthy Me, a lifestyle management program offered to patients at Eskenazi Health in Indianapolis.

Brown began taking classes on nutrition and exercise. For the first time in his life, someone took the time to help him learn how to be healthier.

“I never had anybody instruct me or try to help me with my food conditions,” he said. “I appreciate what they’re doing for me.”

He has dropped nearly 40 pounds in the past six months and his diabetes has come under better control, though he still has 70 more pounds to go to get below the 220 he weighed in high school.

“I think I’d feel better and get off all this medication I’m on,” he said, adding that he still takes 16 pills a day. “I always wanted to be slim. I’m embarrassed about the fat on my belly, the fat on my arms, on my chest.”

So now he reads nutrition labels and attends low-impact exercise classes three days a week. He has cut way back on salt and learned to control his portions – eating “on a saucer” instead of several dinner plates at a time. He has given up his daily habit of drinking an entire 2- or 3-liter bottle of soda pop. He saves half for another day.

“It isn’t easy,” said Brown, who moved from his native Terre Haute to Indianapolis three years ago to take care of an ailing uncle. The older mandied this spring.

Healthy weight tips

• Know that it’s not your fault if you’re carrying extra weight. The way the human body evolved, combined with easily available and low-cost processed food make weight gain likely and weight loss challenging.

• Fitness matters more for health than a number on a scale. Find physical activities you enjoy and commit to move a total of least 30 minutes a day, five days a week.

• Make sure to average at least 7 hours of sleep a night. Disconnecting from electronics for 90 minutes before bedtime can help.

• If you’re concerned about weight, prioritize not gaining more and the quality of foods you eat.

• Chose whole foods, like fruits, vegetables, nuts, healthy oils, fermented dairy products and fatty fish, which have a healthier mix of nutrients and make you feel fuller.

Brown doesn’t have friends in his new city and hears from family members only a few times a month. He said some people avoid him because of his size, and he wishes he had a girlfriend or someone to push him a little more. “They’ll go to somebody slimmer or looking better.”

Where he lives, there are no groceries within walking distance, and the nearest place with food, a Dollar General, doesn’t carry fresh fruit.

His goal now is to build up enough strength to be able to work out at a gym, though the closest one is 5 miles away, and with gas hovering near $5 a gallon, he’s not sure he’ll be able to get there very often.

“I’m doing the best I can,” he said.

The weight of inequality

Clark, of Indiana University, recently helped lead a study trying to unpack the habits, behaviors and patterns that lead to weight gain among people of limited income.

All the participants were enrolled in Healthy Me, the same program Brown joined, and half received eight to 12 text messages a day asking about their food and exercise-related activities and offering tips for healthier behaviors.

Neither group lost weight by the end of the six-month study.

Clark said he’d like to try again with a younger group of people, less trapped by their habits and with less weight to lose.

He was surprised at how much weight many of the participants were carrying. The mean body mass index of the group was 45, substantially above the cutoff for obesity of 30. An average-height woman, at 5-foot-5, would have to weigh more than 270 pounds to reach a BMI of 45.

For 30 years our field’s been doing behavioral counseling for weight loss. It’s total nonsense. It’d be an inhuman amount of self-control to achieve (weight loss) and sustain it. Why we’ve kept on with this line of work just baffles me.

Many of the participants had hypertension and diabetes; most were nonwhite.

They were not healthy people, Clark said, and unfortunately, his study did not uncover “actionable” patterns or ways to help them get healthier. Participants, he said, had accumulated disadvantages over generations and the course of their lifetimes and were still plagued by limited access to healthier foods and activities.

One thing it showed again, he said, is that even with support, losing weight is incredibly hard.

“For 30 years our field’s been doing behavioral counseling for weight loss. It’s total nonsense,” he said. Biology and a lack of resources makes it nearly impossible for someone carrying dozens of extra pounds to make themselves thin. “It’d be an inhuman amount of self-control to achieve (weight loss) and sustain it. Why we’ve kept on with this line of work just baffles me.”

Making a difference at a national level requires many more programs like Healthy Me, he said, and dramatic changes from government and industry.

It’s not just obesity or poverty or racism that’s fueling the poor health of Americans, Clark said.

“It’s not one factor,” he said. “It’s the inequality itself.”

Cultural context matters

Stress contributes to obesity at a biological level by causing the body to hold on to nutrients as well as by “provoking behaviors that are obesogenic,” such as overeating, said NiCole Keith, a physical activity researcher and Clark’s collaborator at Indiana University and the Regenstrief Institute.

Poverty makes life more stressful. So does racism.

“Being a minority in America is stressful – full stop,” Keith said.

People without economic resources lack the discretionary income to spend on healthy food or workout clothes. They don’t have the time to exercise or live in neighborhoods where it’s safe to go for a walk. They don’t have backyards where they can grow fresh fruits or vegetables.

“Even if you have access to healthy food or you have a community garden in your neighborhood,” Keith said, “if you’re not used to tasting this other kind of food, or you’re not used to the discomfort of sweating … you’re not going to do it.”

There also are cultural factors that might stand in the way of living a healthier lifestyle, she said.

Obesity is “steeped in generations,” Keith said. Some people expect they’ll gain weight because all their relatives and friends have, or they cook the way they do because that’s the way their family always has.

It can be seen as rude to turn down food someone offers, she noted. And “if you tell somebody ‘I’m on a diet,’ they say, ‘Oh, you look beautiful,’ or ‘You’re perfect – why do you want to change?’ Or for people of color, ‘Why are you succumbing to European standards of what’s beautiful?'” Some cultures view excess weight and lack of exercise as an indication of wealth and social status.

Mulugeta said he treats many immigrant patients who have different views of healthy weight and diet than American health care providers. Doctors, he said, must respectthese patients’ backgrounds and perceptions to care for them effectively.

“We have to come with an understanding of the cultural context and meeting patients where they are,” Mulugeta said, “and discussing the reasons why we as medical professionals are concerned with excess weight.”

Research suggests food advertising has a bigger effect on Black kids than their white counterparts.

On TV alone, Nielson data from 2019 found Black youths see 75% more fast food ads than their white counterparts, nearly 1,000 a year. And that doesn’t include social media, which tends to attract more Black and Hispanic young people, said Shiriki Kumanyika, a research professor at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University, who is leading a new national campaign called Operation Good Food and Beverages that addresses such advertising.

Black young people may be particularly responsive to seeing themselves in a positive light in food ads. Advertising, she said, “normalizes unhealthy eating in ways that can become part of your identity – what people like you are supposed to be eating.”

Instead, her group, supported by a youth advisory panel basedin Baltimore, sees healthy eating as a way to stand up for racial identity, challenge the existing food environment and tie into a positive message of social justice, she said.

“Of course, this is good for all communities,” not just Black communities, Kumanyika said. “But because we have more of the problem and less of the solution, we decided we’d better take the lead on this.”

Finding solutions

Ultimately, every effort to combat obesity will fail if healthy foods aren’t made less expensive, said Marlene Schwartz, director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health at the University of Connecticut.

“If people can’t afford to eat the healthy food,” she said, “none of the rest of it really matters.”

Economic support could prevent food insecurity and allow people like Nathaniel Brown to afford healthy food such as fruits and vegetables, Drewnowski said.

“The way not to go in my opinion is local, organic, minimally processed salads that you prepare at home after you’ve come back from two jobs.” That’s just not realistic, he said. Nor is everyone growing vegetables in their backyard. Not everyone has a backyard.

The U.S. government simply needs to do more to help combat obesity, said nutrition and public policy expert Nestle.

“They should be frantic about obesity,” she said. “They should be up in the middle of the night worrying about what’s going to happen as it becomes normalized in society and more and more people put on more and more and more weight.”

Discouraging people from eating “junk” food by raising taxes and limiting marketing can be helpful, she and several other experts said.

Expanding nutrition labels also makes it easier for people to identify unhealthy food. At the end of June, Canada announced that as of Jan. 1, 2026, food high in saturated fat, sugars and sodium must carry a label on the front of the packaging.

In Chile, similar front-of-package labeling led people to purchase 24% fewer sugary drinks over 18 months, and more than one-third of Chileans said the labels encouraged them to change their eating habits.

No one thing that we consume uniquely causes weight gain. It’s the totality of what we consume.

But the COVID-19 pandemic provided a stark reminder that people are resistant to public health interventions, said Ted Kyle, founder of ConscienHealth and former chair of the Obesity Action Coalition, a 75,000-member nonprofit that works to empower people living with obesity.

Public health measures don’t always work, either. “For the past four decades, we have implemented a lot of public health policies based on what we presumed would work, and it has turned out it doesn’t,” he said.

There was the low-fat craze and then the push to eliminate added sugar from the diet. Sugar consumption has declined dramatically since 2000, yet the prevalence of obesity has continued to climb.

“No one thing that we consume uniquely causes weight gain. It’s the totality of what we consume,” Kyle said.

For his part, Clark said every hospital in the country could be offering personalized programs such as Healthy Me to help people like Brown learn and practice healthier habits.

The obesity epidemic, he said, “isn’t going to be solved at the individual level.”

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

As part of our ongoing commitment to help our patients live their best life we are sharing the full USA Today series on “Rethinking Obesity”. The following is #2 in the series.

ILLUSTRATION BY TRACIE KEETON/USA TODAY; AND GETTY IMAGES

Karen Weintraub USA TODAY

Published 5:00 AM EDT Jul. 26, 2022 Updated

Editor’s note: Part 2 of a six-part USA TODAY series examining America’s obesity epidemic.

Tigress Osborn is fat, and she’s OK with that.

What she’s not OK with is how she and others with excess weight are treated as if they’re lazy, stupid and sick.

“We consider fat a part of human body diversity,” said Osborn, chair of the nonprofit National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance.

She insists on using the word “fat” rather than the more politically correct “person with obesity,” which she believes characterizes people with extra pounds as abnormal or unhealthy.

Many of the problems people blame on obesity might instead be the fault of something else, she said.

Take COVID-19. Research found obesity played a role in 30% of severe cases of the disease. But, Osborn suggested, what if the story is really that fat people waited too long to seek medical care because they’re so used to being poorly treated by the health care system? Or maybe fat people who exercise or follow a certain diet have a different risk profile, but the message is just “all fat people are at risk.”

“It’s impossible for us to know whether some of the things that are blamed on fat are caused by weight stigma or other forms of oppression,” she said, citing anti-poverty bias and racism.

Every facet of society – including the medical community – has failed fat people, Osborn and others said.

Rethinking Obesity

Despite decades fighting America’s obesity epidemic, it’s only gotten worse. To try to understand why, USA TODAY spoke with more than 50 experts for this six-part series, which explores emerging science and evolving attitudes toward excess weight.

Researchers have focused on what’s wrong with being fat, rarely exploring why some people remain healthy regardless of excess weight. Doctors have told those with extra pounds they need to lose weight but haven’t offered them a realistic method for doing so.

In 2005, U.S. Surgeon General Richard Carmona declared obesity a bigger threat to America than terrorists, but government has done little to rein in food marketing, reduce demand by increasing taxes or adding the kind of nutrition labels shown to decrease “junk food” consumption in other countries.

The law offers little protection. It remains legal in 49 states to fire people simply for their size.

And stigma against excess weight remains in every corner of life even as 42% of Americans fit the medical definition for having obesity. (Obesity is defined as a body mass index – a measure of height and weight – of 30 or above. A 5-foot-5 woman would be considered to have obesity if she weighed more than 180 pounds.)

“We know that shaming people to lose weight doesn’t work,” said Osborn, 47, a full-time advocate for fat people’s rights. It hasn’t for the 40 years of the declared obesity epidemic or decades of research before that. Yet weight bias continues.

A warning sign or disease itself?

The medical community leaves little doubt that carrying extra pounds can lead to serious health problems. Many types of cancer are linked to obesity. So is heart, liver and kidney disease. People with obesity run an 80% higher risk of developing diabetes than those without it.

In 2013, the American Medical Association defined obesity as a disease itself. They wanted to finally bring attention to the idea that people are not to blame for their excess pounds, that fat people are not lazy or dumb, just suffering from an illness.

But Osborn is tired of being defined as sick when she’s not.

She points out that “being fat and having a health challenge is not the same thing as having a health challenge that is created by being fat.”

Researchers could learn a lot, she said, by looking at people with excess weight who don’t develop diabetes.

“When fat people don’t have the problems we think are caused by fat, we dismiss them as an anomaly,” she said. ”There is no money to be made in telling people they’re fine the way they are.”

The assumption of poor health can have serious consequences.

Before having surgery last summer, Osborn needed a cardiologist’s clearance. After asking what she had done to lose weight, the cardiologist glanced at her EKG and said it suggested she’d had a heart attack.

Osborn freaked out. Her surgery nearly canceled, she was scheduled for further testing and prescribed a drug that made her feel sick for weeks.

The operation went fine, and when seeing a different cardiologist afterward, she asked about the supposed heart attack. “Oh no,” he told her. “Those kinds of readings happen all the time when an electrode isn’t placed properly.” He took her off the medication.

“It was very clear to me that that all would have gone very differently if I had walked into that office not looking like I look,” Osborn said.

“Not everything going on in (a fat person’s) body is because of their fat. And what the doctor assumed was going on in my fat body wasn’t even going on.”

Many of the studies that tie health problems to excess weight don’t adequately consider other possible causes of those problems, said Ragen Chastain, an advocate, researcher, speaker and author of ”The Weight And Healthcare Newsletter.”

For instance, yo-yo dieting, practiced by people desperate to lose pounds but destined to regain them, has been shown to cause some of the health problems otherwise attributed to excess weight.

“Well-intentioned people have been duped,” Chastain said, by the assumption that all weight gain is bad and weight loss good.

When people don’t lose weight with lifestyle changes, the assumption is it’s because they’re not trying hard enough, which is then used to stigmatize them even further, Chastain said.

Research shows people can be heavy without being sick.

“There’s a subgroup of people with obesity but without indicators of poor health where I wonder what the rationale would be for treating them,” said Kevin Hall, an obesity researcher at the National Institutes of Health.

He noted they might run a higher risk for health complications in the long run. But people with very little body fat face many of the same health risks. “Body fat has a reason,” Hall said.

More than a number on a scale

Glenn Gaesser has been arguing for more than a quarter century that fitness does a far better job of predicting health than weight.

Sedentary people of “normal” weight have worse health outcomes than fat people who exercise regularly, he said.

Technically, fitness is measured by oxygen use while on a treadmill, so it’s too complicated to be widely adopted, said Gaesser, a professor of exercise physiology in the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University.

But most people can reach at least minimal fitness by moderately exercising 150 minutes a week, or briskly exercising for 75 minutes a week. “The biggest benefit comes from getting people from a ‘couch potato’ status to some level of activity,” he said. “It’s not like getting ready to run a marathon.”

Exercising improves the health of virtually every major cell type in the body, he said, including fat cells. There’s clearly something biological about fitness. In mice, transplanting fat tissue from fit animals into sedentary ones improved the recipient’s metabolic health.

Size does not determine risk for people with good cardiovascular fitness, Gaesser and a colleague concluded in a 2021 article. Most heart disease risks associated with obesity can be improved with exercise, independent of weight loss. And it’s yo-yo dieting, not simply excess weight that poses serious heart health risks, they concluded.

“If we just try to focus on the behaviors and encourage those people to engage in more physical activity, their health would improve,” Gaesser said.

With COVID-19, the apparent higher risk of infection and disease severity might have been more about the patients’ fitness levels than their weight, Gaesser said, citing a 2020 study that concluded as much. “It wasn’t the fatness that was the predictor, it was the unfitness,” he said.

Although having obesity can make exercise more challenging at first, Gaesser said, his research and experience suggest people of any size, even with a very high weight-to-height ratio, “can improve their fitness level just as much as anyone else.”

Weight stigma, a public health issue

With so many Americans carrying extra pounds, it seems logical that society would be getting more accepting of heavier people.

But it isn’t, according to Rebecca Puhl, who has studied the subject for decades.

The public perception is that shaming people for their size will provoke them to lose weight. “We see the opposite,” said Puhl, deputy director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health at the University of Connecticut.

Some advertisers have evolved, offering plus-sized models, which Puhl supports. But “we still have very stringent societal ideals of thinness,” she said, and people who violate those ideals are considered lazy and lacking in willpower.

Shame and stigma cause psychological and emotional distress, anxiety and low self-esteem, all of which can lead to disordered eating and extra pounds, she said. People of all races face weight stigma, though racism compounds the ill effects of weight prejudice.

Weight stigma itself is a public health issue. We need to shift societal attitudes that are strongly ingrained and have been for decades.

“Weight stigma itself is a public health issue,” Puhl said. “We need to shift societal attitudes that are strongly ingrained and have been for decades.”

In survey data across nations, more than half of those with obesity point to family members and doctors as the biggest sources of “fat shaming.”

Historically, weight stigma wasn’t “on the radar” for doctors or medical students, she said. But in 2020, more than 100 medical organizations committed to ending it. “There’s a recognition that we need to address this.”

Now, some of the stigma is coming from the other side as well, with people getting blasted on social media and elsewhere for going public with their attempts to lose weight.

Ted Kyle takes issue with both the people who contend obesity is a crisis and with those who say it poses no problem at all.

Research has clearly established that obesity can undermine health. But that doesn’t justify policing other people’s weight, said Kyle, founder of ConscienHealth, which promotes sound approaches to health and weight.

Obesity is a long-term health problem; stigma and bias do their damage in the short term, he said.

“When you tell someone their health, their body is a disaster, it’s not helpful. It does cause immediate harm,” said Kyle, also a former chair of the Obesity Action Coalition, a 75,000-member nonprofit advocacy organization.

“The media and public health needs to stop catastrophizing obesity.”

There’s no question excess weight increases the risk for disease, but Kyle doesn’t see it as a crisis that can be resolved quickly. The language of emergency reinforces bias against large people, he said.

Help fight the stigma against obesity. Share this story.Share on Facebook

Science hasn’t yet figured out how to solve obesity, at least not at the population level.

“All the while when we’ve been pursuing food and physical-activity-based solutions, the rate of obesity keeps rising,” he said. “We don’t know how to blunt the rise in obesity because we don’t know precisely what the factors are (that are causing it).”

The type of food people eat may play a role, along with stress, additives and a host of other factors.

At the individual level, Kyle said, obesity medicine specialists have made a lot of progress in helping people lose weight, but many of those approaches aren’t covered by insurance – at least not without the kind of lobbying that is difficult for all but the most advantaged patients to muster.

Osborn said she understands why people opt for weight loss medications or surgery if their doctor regularly tells them they’ll die without it. But counseling patients on how to be healthy at any size would be safer and less stigmatizing, she said.

“People living in a fat-phobic culture are going to resort to things that will help them move away from that oppression,” Osborn said. “They’re making a tough choice in a culture that’s telling them their body is hate-able.”

Fat people, Osborn said, “just want to live our best lives.”

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

At Winterberry we are dedicated to helping our patients live their best life. Part of that commitment is highlighting the truth about obesity, its causes and effective, proven medical treatments.

We are republishing a comprehensive series of articles that first appeared in USA Today. Our hope is that these articles will give anyone suffering from the disease of obesity new information and relieve because as our Medical Director, Dr. Steven Zizzo says, “It’s Not Fault”.

Series Introduction:

More than 4 in 10 Americans now fit the medical definition for having obesity, putting them at risk for serious health problems, including diabetes, heart disease and some types of cancer. The pandemic increased the stakes. In its first year, nearly one-third of severe COVID-19 cases were blamed on excess weight.

USA TODAY decided to take a look at how America’s weight has been changing in recent years, including advances in treatments and the scientific understanding of obesity. We spoke with more than 50 experts – in nutrition, endocrinology, psychology, exercise physiology and neuroscience – and people who are intimately familiar with the challenges of extra pounds.

The answers aren’t simple.

But they get to the essence of America: our issues with race, stigma, personal responsibility, economic stability and the power of corporations.

Karen Weintraub USA TODAY

ILLUSTRATION BY TRACIE KEETON/USA TODAY; AND GETTY IMAGES

Published 5:02 AM EDT Jul. 26, 2022 Updated

Barbara Hiebel carries 137 pounds on her 5-foot-11 frame. Most of her life she weighed 200 pounds more.

For decades she tried every diet that came along. With each failure to lose the extra weight or keep it off, her shame magnified.

In 2009, Hiebel opted for gastric bypass surgery because she had “nothing left in the gas tank” to keep fighting. She quickly dropped 200 pounds and felt better than she had in ages.

Over the next eight years though, 70 pounds crept back, and the shame returned.

“I knew everything to do to lose weight. I could teach the classes,” said Hiebel, 65, a retired marketing professional from Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She asked to be identified by her first and maiden name because of the sensitivity and judgment surrounding obesity.”I’m not a stupid person. I just couldn’t do it.”

The vast majority of people find it almost impossible to lose substantial weight and keep it off.

Medicine no longer sees this as a personal failing. In recent years, faced with reams of scientific evidence, the medical community has begun to stop blaming patients for not losing excess pounds.

Still, there’s a lot at stake.

Rethinking Obesity

Despite decades fighting America’s obesity epidemic, it’s only gotten worse. To try to understand why, USA TODAY spoke with more than 50 experts for this six-part series, which explores emerging science and evolving attitudes toward excess weight.

Obesity increases the risk for about 200 diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, asthma, hypertension, arthritis, sleep apnea and many types of cancer. Obesity was a risk factor in nearly 12% of U.S. deaths in 2019.

Even for COVID-19, carrying substantial extra weight triples the likelihood of severe disease.

Early in the pandemic, pictures from intensive care units repeatedly showed large people fighting for their lives. At Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City, the average age for ICU patients was 72 if their weight was in the “normal” range and just 58 if they fit the medical definition for having obesity, said Dr. Louis Aronne, an obesity medicine specialist there.

As fat cells expand, the body produces inflammatory hormones. Combined with COVID-19, the inflammation creates a biological storm that damages people’s organs and leads to uncontrolled blood clotting, Aronne said.

The link between obesity and severe COVID-19 is surprisingly strong, said Dr. Anthony Fauci, who has dedicated his life to combating infectious diseases.

“The data were so strong,” Fauci said of a recent government study. Even for children, every increase in body mass index led to a greater risk of infection with COVID-19 and for a dangerous case of the viral illness.

0:00

1:57

Why are obesity rates so high in America? Learn the causes and why it’s so tough to cure.(1:57)

Obesity rates are weighing down America. Why is it so hard to cut down the pounds? We look into the causes and challenges.

“The more you learn about the deleterious consequences of obesity, the more reason and impetus you have to seriously address the problem,” Fauci said.

But despite more than 40 years of diets and workouts, billions of dollars spent on weight loss programs and medical care, and tens of millions of personal struggles like Hiebel’s, the obesity epidemic has only gotten worse. Nearly three-quarters of Americans are now considered overweight, and more than 4 in 10 meet the criteria for having obesity.

To try to understand why, USA TODAY spoke with more than 50 nutrition and obesity experts, endocrinologists, pediatricians, social scientists, activists and people who have fought extra pounds. The reporting resulted in a six-part series, which explores emerging science and evolving attitudes toward excess weight.

The experts pointed to an array of compounding forces. Social stigma. Economics. Stress.Ultra-processed food. The biological challenges of losing weight.

They agree people need to take responsibility for eating as well as they can, for staying fit, for sleeping enough. But simply promoting individual change won’t end the obesity epidemic – just as it hasn’t for decades.

It’s time to rethink obesity, they said.

Experts offered different ideas to change the trajectory.

Subsidize healthy food. Make ultra-processed foods healthier or scarcer. Teach kids to better care for their bodies. Provide insurance for prevention instead of just the consequences. Personalize weight loss programsto support, not stigmatize. Learn what makes fat unhealthy in some peopleand not in others.

For real progress to come, they agreed, society must stop blaming people for a medicalcondition that is beyond their control. And people must stop blaming themselves.

“There’s a lot of misperception among patients that they can somehow ‘behavior’ their way out of this – if they just had enough willpower and they just decided they were finally going to change their ways, they could do it,” said Dr. Sarah Kim, an endocrinologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

For the vast majority, trying to will or work themselves to thinness is just a prescription for misery, she said.

“There’s so much suffering associated with weight that is just so unnecessary.”

Origin story

Like many people who struggle with weight, Hiebel has a family tree that includes others with extra pounds. Her mother was heavy, as were other female relatives.

In childhood, Hiebel simply loved food. It gave her pleasure. A buzz.

In fourth grade, her mother brought up her weight with the pediatrician. He prescribed amphetamines.

I was a fat kid who always wanted to be skinny. My whole life. I wanted to be healthy. Thinner.

“I was a fat kid who always wanted to be skinny,” Hiebel said. “My whole life. I wanted to be healthy. Thinner.”

She blamed herself. For not pushing away from the table sooner. For enjoying what she ate. For the thoughts about food that popped into her head every 30 seconds all day long. For not being able to throw away the plate of cake until she had devoured every bite.

Even though she was trained as a nurse, Hiebel, was petrified of getting medical care. “I spent 50 years largely avoiding doctors because they’re going to weigh me,” she said.

People who experience and internalize weight stigma are more likely to avoid health care and report lower quality of medical care, research shows.

Many fear the waiting room won’t have chairs strong enough to support their weight. They won’t fit on the examining table. The doctor will mock or criticize them for being overweight without offering realistic advice for how to lose their extra pounds.

“We treat them as if we obviously don’t care because obesity must be their fault,” said Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital. “We just tell them to eat less and exercise more, and when that fails, as it does 95% of the time, we don’t do anything about it.”

And people with obesity continue to punish themselves. Stanford tells a story about a patient whose weight kept climbing even after being prescribed medications that are usually effective.

The woman confessed she wasn’t taking the prescription because she hadn’t tried hard enough to lose weight on her own and didn’t deserve it. “I only do 15,000 steps a day,” the woman told Stanford. “I feel like I should be doing 20,000.”

Stanford ended up persuading her to take the medication. She explained that if someone had a disability weakening their legs, it wouldn’t be a failure for them to use a wheelchair.

Compassionate care

Hiebel had excellent insurance coverage, but she remembers overhearing her internist arguing with the insurance company to get her weight loss surgery covered. She was required to try Weight Watchers for at least six months and a second weight loss program for another six months, although data shows the vast majority of people can’t lose substantial weight and keep it off.

It felt as if the whole insurance industry was telling her she was guilty for being fat.

Shame and embarrassment led Hiebel to avoid seeking help when she started regaining weight after the surgery. “People did all this work on you. You spent all this time and energy and you’re failing yet again,” she said.

But she didn’t want to let all her progress fall apart. She eventually went back to her surgeon.

He told her to make an appointment with Dr. Katherine Saunders at Weill Cornell – and to wait as long as was necessary to see her.

When Hiebel eventually found herself in Saunders’ office, she heard for the first time in her life the words: “This is not your fault.”

“In my head, I’m going, ‘Of course it’s my fault. I’m weak. I’ve got no willpower,'” Hiebel said.

Saunders told her weight loss would take hard work. Her body was conspiring against her to keep on the pounds. The free snacks in her office break room would be a constant temptation.

She offered Hiebel some new tools, including medication to address metabolic issues and her mental state.

With other weight loss doctors, Hiebel felt embarrassed to return for another appointment until she had lost 10 pounds. That often meant never going back. But Saunders told Hiebel to call immediately if she started to struggle.

“She was inoculating me against that from the beginning,” Hiebel said. “‘This isn’t your fault. I can help. And if you get into trouble, don’t do what you would normally do and actually call me.'”

Trouble losing weight? You’re not alone.

The medication gave Hiebel some stomach problems. Saunders warned her that might happen and told her to tough it out for a few weeks. They would adjust the dosage or prescription if it got too bad.

Hiebel’s pounds started melting off. She felt great.

Then, for two days, Hiebel found herself repeatedly standing in front of her pantry. “Just looking,” she said. “I’d grab a cracker or shut the door. But you keep going back.”

Barbara Hiebel, who has struggled with her weight since childhood

I always felt controlled by food. Everything was about not eating.

Without noticing, she had missed two daily doses of Contrave, a prescription weight loss pill that also helps with mood disorders. Hiebel resumed taking the pills, and her pantry-gazing ended. “I went back to my normal habits almost overnight. Literally.”

That’s when she realized the power of the medications – and of the drive she carried within her.

“I always felt controlled by food,” she said. “Everything was about not eating.”

But the metabolic changes from the surgery and the boost from the medications finally changed that dynamic. Raw cookie dough, once her “fifth major food group,” lost its grip on her mind. “I kind of don’t really want it,” she said.

She can throw away a piece of cake after just a few bites, even leaving behind the icing. “Now I’m that person,” Hiebel said, “not because I somehow have the willpower, but because I don’t really want it.

“I feel liberated around food.”

Easy to gain, hard to lose

Weight gain may be as simple as consuming more calories than you burn, but weight loss isn’t as simple as burning more calories than you eat.

The human body evolved over tens of thousands of years to hold on to excess calories through fat.

“The default is to promote eating. It’s very simple, very logical. If it were not this way, you would die after you’re born,” said Tamas Horvath, a neuroscientist at the Yale School of Medicine. “When you live out in the wild, you need to be driven to find food, otherwise you’re going to miss out on life.”

Severe calorie restriction is dangerous, said Horvath, who, with his colleague Joseph Schlessinger, has been studying the brain wiring that drives hunger.

In a study of mice whose calories were severely restricted, one-third lost weight and lived longer, as the experiment set out to prove, Horvath said. But nothing happened to another third. The remainder died young.

Dr. David Ludwig, an endocrinologist and researcher at Boston Children’s Hospital

You have to keep restricting more and more to keep losing weight. This is a battle between mind and metabolism that most people don’t win.

Restricting calories seems to slow metabolism, meaning the body needs less fuel. “You have to keep restricting more and more to keep losing weight,” said Dr. David Ludwig, an endocrinologist and researcher at Boston Children’s Hospital. “This is a battle between mind and metabolism that most people don’t win.”

Genetics play a role, too. Some people seem destined from birth to be thin, like everyone else in their family.

Only about a quarter of the population, those with a genetic gift for thinness, seem to escape extra pounds in today’s food climate. Even these lucky few can develop the same metabolic problems seen with obesity, becoming “thin outside, fat inside,” according to Jose Ordovas, a professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University.

And everybody doesn’t gain the same amount of weight from overeating.

A 1990 study showed that a group of identical twin men fed an additional 1,000 calories a day for three months led some to gain roughly 10 pounds and others to gain 30. The twin pairs varied substantially from each other in how much weight they gained and where, but each twin responded nearly the same as his brother.

Overeating can distort the nerves in the brain that receive signals from hormones, said Aronne, at Weill Cornell.

“As you get more damage there, fewer hormonal signals are able to get through and tell your brain how much you’ve eaten and how much fat is stored,” he said. “As a result, your body keeps expanding your fat mass.”

Exercise doesn’t lead to weight loss either. “You can’t easily exercise off obesity,” said Marion Nestle, an emerita professor of nutrition and food science at New York University.

Still, experts agree that regular exercise is crucial to health at any size. And it may help prevent weight gain and regain.

“The Biggest Loser” TV show ran on NBC for 17 seasons, following participants as they lost weight through diet and exercise. In 2016, Kevin Hall, a National Institutes of Health researcher, examined what had happened to 14 of the 16 contestants from the 2009 season.

All but one regained some or all of their lost weight, Hall found. But the contestants who remained the most physically active kept off the most weight, he reported in a 2017 analysis of the results.

Kevin Hall, a National Institutes of Health researcher

The benefits of exercise when it comes to weight don’t seem to show up so much while people are actively losing weight, but in keeping weight off over the long term.

“The benefits of exercise when it comes to weight don’t seem to show up so much while people are actively losing weight,” he said, “but in keeping weight off over the long term.”

Adequate sleep also is essential for maintaining a healthy body weight and can help with weight loss, studies show.

To accomplish everything she wanted to do in a day, Hiebel often limited her sleep to five to six hours a night. Her solution to the resulting exhaustion was to snack. She remembers frequent coffee and cookie breaks, “as self-defeating as that is.”

Many people make the same decision to sleep less – and end up eating more.

In a study published earlier this year, people who had extra weight but not obesity were encouraged to sleep 1.2 hours more a night for two weeks. They ended up consuming 270 calories less a day than the volunteers who slept their typical 6½ hours or less a night.

“It’s about sufficient sleep making you feel less hungry, making you want to consume fewer calories,” said Dr. Esra Tasali, who led the study and directs the UChicago Sleep Center. “Basically not eating the extra chocolate bar.”

Growing hope

Even though she knows how to work the system from her years in the insurance industry, Hiebel is struggling again to get her medication covered by insurance.

She may have to switch to two low-cost generics, provided at the wrong dose. “I’m going to have to cut a pill into fourths with a razor blade,” she said. “It’s ridiculous.”

But Heibel will do what she must to keep off the extra weight.

She feels healthier without those pounds. She used to dread the hills she faced on hikes with her husband. After losing weight, she barely notices them.

“We’re not talking about Everest,” she said. “I’m not running marathons, but I can do this stuff and I don’t huff and puff.”

Before she started weight loss medications, she was heading into pre-diabetes. She had borderline high cholesterol and was managing hypertension. Now, her LDL and HDL hover around 70; 60 to 100 is considered optimal.

Just knowing it was possible to break food’s grip on her life, that there was hope, was transformative.

Hiebel wants to talk publicly about her story, about the shame she endured for decades, because she wants others to know it’s not their fault and help is out there.

The incident with the Contrave made her realize she’ll probably need to take a constellation of medications forever. And they still give her a rumbly tummy sometimes.

It’s a small price to pay, she said, “to do something that for 50 years I wasn’t able to do.”

“I’m happy as a clam, and I’m not looking back.”

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

During PRIDE month we sat down for a conversation with Shanna. Shanna is one of our team members who work with and support our LGBQT patients.

Q: What role do you have at Winterberry?

A: I am a primary care nurse practitioner at Winterberry and I work directly with our LGBQT patients as well as patients who are questioning their orientation or gender.

Q: Is there special training involved in working with such a diverse population?

A: I have done extra training through Rainbow Health Ontario to become certified in Gender Affirming Care in the adult population.

Q: How do you support LGBQT and questioning patients?

A: I provide gender competent care and hormone therapy. I have discussions with patients and their families about gender identity. We discuss health and gender related goals so that I can best assist their needs.

Q: What is involved in gender affirming care?

A: It can include hormone therapy and surgical referrals as well as ongoing support and assistance where needed.

Q: Are you the only team member at Winterberry with a focus on LGBQT patients?

A: Right now, yes, but we will be training more staff in the near future which is exciting!

Q: What’s the benefit of LGBQT patients receiving care specific to their unique needs?

A: Patients who receive LGBQT competent care develop better therapeutic relationships with their provider and are able to have both their health and gender needs met.

Q: Are there common reasons why LGBQT patients don’t receive the care they need in other settings?

A: Common reasons that patients don’t receive care for their unique needs include stigmatization, negative prior experiences with health care, higher rates of anxiety and mood disorders, and difficulty openly discussing their gender and sexual health related issues. I know this because in my practice, when I initially meet patients, many have expressed negative experiences in healthcare in the past. It is important to trust and have confidence in your health care provider so during my appointments we work towards rebuilding that patient-provider and patient-health relationship.

Q: What’s the goal for your patients?

A: To be confident, happy and healthy!

Meet Dinisha. She’s a Winterberry Family Medicine Nurse Practitioner who works closely with our senior patients. Her goal is to ensure seniors in our care have the accurate information and healthcare they need to live their lives as actively and happily as possible.

We caught up with Dinisha in June and asked her a few questions:

Q: What is your role in the Clinic and how does that fit into working with senior patients?

A: I am a primary care Nurse Practitioner focusing on health promotion, disease and injury prevention, cure and rehabilitation. Through my experience working in palliative care, I have taken a focus with our senior patients.

Q: What kind of “senior-specific” services does Winterberry offer?

A: Winterberry provides holistic care by acknowledging the physical, emotional, social and spiritual wellbeing of all our patients, including seniors. Our team is composed of highly skilled dieticians, social workers, counsellors, nurses, doctors, nurse practitioners and physician assistants who have been trained to assess and treat our seniors well. Winterberry acknowledges the burden our seniors have with managing their chronic health conditions and provides home visits by Nurse Practitioners. Providing options of home visits for health care management not only aids in addressing their physical well being, but also their mental health.

Q: What unique needs do seniors have that other patients do not?

A: The needs that our patients have while aging may include financial security, personal security and safety, health care and health challenges, mental health, and self-actualization. At Winterberry we work together with the patient to best address all their needs all while preserving their dignity and autonomy.

Q: Are there common reasons seniors don’t get the care they need? Obstacles that prevent them from living as long and healthily as possible?

A: Often seniors do not get the care they need due to difficulties attending their appointments. With changes in mobility, vision, hearing, cognition, pain and strength, attending an in-office appointment can be very difficult. With patients living in long term care facilities, assisted living and/or living at home alone, transportation is the biggest concern. Due to missed appointments and/or inadequate follow ups, their concerns get unseen and as a result, built up. At Winterberry we work with senior patients, no matter where they live, to ensure they have access to the care they need.

Q: During the pandemic were there specific things Winterberry did to ensure our senior patients continued to be well cared for?

A: During the pandemic, we set up routine scheduled calls to check in with our senior patients. We eased the sense of isolation through these frequent calls, providing compassionate and charismatic telephone calls regardless of if there were physical health concerns needing medical attention vs a mental health check in.

Q: Any last thoughts on serving seniors?

A: We love and value our seniors here at Winterberry Family Medicine!

COVID-19 fueled stress-related unhealthy eating habits that have resulted in expanded waistlines for almost half of North Americans.

Forty-eight percent of Americans packed on extra unwanted pounds during the pandemic (the average weight gain was 29 pounds) while 42% of Canadians gained an average of 6-15 pounds.

This doesn’t come as a big surprise when you consider diets, activity levels, sleep habits, and daily routines were turned upside down by the pandemic

The study on American weight gain found those who gained the most were more likely to be male, married, 45 or older with a full-time job. It also found that people were more likely to have gained weight if they were overweight before the pandemic and/or had depression.

“Even before the pandemic, stress was a major determinant of unhealthy lifestyles in adult Americans, and the problem continues to worsen for certain groups,” said study lead Jagdish Khubchandani, a public health professor at New Mexico State University.

Children gained excess weight as well, due to disrupted routines, increased stress and less opportunity for physical activity and good nutrition.

A study by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention found that the percentage of obese children and teens increased to 22% during COVID.

It’s natural to experience self-recrimination and self-blame about the changes in one’s weight and to be affected by societal stigma around being overweight. But it’s important to remember pandemic weight gain has affected a huge percentage of the population and self-compassion is in order.

For those who want to lose weight, action is in order as well. Here are 5 steps you can take to try to bounce back after COVID-19, so you begin to feel — and look — more like your old self:

- Set small goals: Consider modest steps you can take that will lead to success. Perhaps eliminate cream from your daily coffee or forgo dessert during the week. Go for a short walk every night after dinner or lift weights at the gym just once or twice a week. Small daily changes can add up to a positive effect on overall health.

- Try something new: Create a new healthy routine for yourself — perhaps go to bed an hour earlier at night, or take up bike riding or pickleball. Team up with a buddy for regular exercise. Try out some healthy new recipes. Shaking things up can help you shed the pounds.

- Do a kitchen purge: If junk food is accessible, you are likely to eat it. Set yourself up for success by replacing foods such as chips, sweets and processed foods with healthier options that are easy to grab when hunger strikes — a banana with almond butter or baby carrots and hummus, for example.

- Monitor your progress: Use digital apps to track your food intake and physical activity or write down the details with old fashioned pen and paper. Studies show that self-monitoring is associated with higher rates of weight loss and with maintaining weight loss over time.